Dickon Hinchliffe is a founding member of the band Tindersticks, an outfit well lauded for its work on the film scores of Clair Denis. Having branched out on his own as a solo composer for Ms. Denis on Vendredi Soir (2002), a piece of music the Village Voice dubbed an "expectant score that enhances the flavor of skewed enchantment and nocturnal mirage, capturing the fantasy evening's blushing irreality and weak-kneed tingle, down to the final note of bleary, dawning euphoria," he's become a composer of the highest regard amongst film lovers all over the globe.

On assignment from ShortEnd Magazine, I caught up with Dickon to discuss experimentation, subverting conventions & his scores for Claire Denis, Ira Sachs and others.

Barry Jenkins (SM): I was gonna ask how you came to film composing, but I kind of know that piece of the story so let’s jump right in from there. So basically I want to say you came to composing through your band Tindersticks which did Trouble Every Day (2001) and Nenette et Boni (1996) for Claire Denis, is that right?

Dickon Hinchliffe: That’s right, yeah.

SM: So what was the process like for you branching out from the band to work on Friday Night (2002)—or actually, even before you get to that, what was it like scoring a film as a part of a band?

DH: I mean, through the first film, Nenette et Boni, it was all just a totally new experience. We spent the whole time experimenting really. It was a completely new thing for all of us, because it was like, all of a sudden you’re not just making music for yourself. You’re involved with an extra medium, you know, the images. And I suppose I realized at that point that with music for film the biggest difference is that you’re kind of sucked into someone else’s world and being a part of that world, rather than,--we used to make music purely, you know, for ourselves. So it was quite a big switch. And with that first film we were kind of…you know we didn’t have any technology really to do it with, it was literally one of us would be pressing play on the videocassette—

(Barry laughs)

DH: —with the rest of the guys setup in the room and we would just be playing along in a crude, but organic way. In some ways it was a bit of nightmare in terms of how long it took us to do things, and now I can do it rather quickly, but in other ways it was a good way to learn because it was done in a very sort of basic, natural way.

SM: And that was Nenette et Boni, correct?

DH: Yeah, the whole of that score really was kind of based on little songs, a little piece of music that we wrote. We played to picture a little bit, but on the whole it was more getting it the right mood, and feeling then we could record things and we’d, you know, we’d then look at it against picture and film, and we’d try it a bit faster, or, you know, have a chorus out or something. It was very sort of hands on.

SM: Now the song “My Sister,” did that come before Nenette et Boni or after?

DH: That’s from the second Tindersticks album, and Claire Denis, when she approached us to do the film, she’d been listening a lot to our second album when she was writing (Nenette et Boni). And…she liked it enough, that’s when she asked us to work on the film itself.

SM: And then…your progression to Friday Night, taking that on as a solo composer in your own right, how did that come about?

DH: In a way, Trouble Every Day was like a bridge between the two. With Trouble Every DayNenette et Boni. And it’s mainly orchestral so it was scored in a more conventional film score manner. So, in a way doing Vendredi Soir (Friday Night), it wasn’t like a huge jump because I’d sort of just started doing that kind of thing already with Trouble Every Day. It was kind of natural. it was three of us in the band really. We had a song that the band had written a while ago, everything except the lyrics, and I always thought it’d be great for a film soundtrack. It would have been on our third album, but we held it back because it really suited that film. But apart from the song really, I sort of took it on in a more film composer’y way just to sort of, to write and develop and I wrote more to picture than we’d done with

SM: So let’s take a side-step for a second, when you guys were working as the band on Nenette et Boni and Trouble Every Day, did you guys have roles or…was the responsibility spread out evenly or were you even at that point in time taking it upon yourself to act as composer?

DH: I think with Nennette et Boni, it was very sort of…we all kind of had roles in the band anyway, and in a way my role was often more sort of the melodic, arrangement side of things. So with Nennette et Boni, we kind of just staged like a band in a way, like we worked from songs. It wasn’t that different. I feel we got a bit excited by the whole process of watching how music changes images, and therefore the power music has within film. And that’s something I think we all knew, but until you actually do it you, you don’t really know how it actually works. I think then with Trouble Every Day the roles changed a lot, because we all agreed it needed to be a more orchestral score, and because that was more my kind of thing I sort of stepped into the driver’s seat more with that film.

SM: It’s funny, in the commentary track of Friday Night, Ms. Denis states that the reason she went away from the full band as score in the film was because she was going to use the music from the radio as songs and just needed something to link the pieces together. But as I watch Friday Night, in the end your work comes across as very involved in the film.

DH: I think what she probably is trying to say is that she wanted the film score to almost feel like it’s coming out of the radio as well, so that the two things sort of would bind together and not feel like, “Oh this is something on the radio now and then this is something that’s film score.” Some pieces are on the radio and then other pieces, a couple of classical pieces that you’re not sure if it's something I did or if it was a piece on the radio. It was kind of innate playing around with conventional source music and score, and sometimes what I’d done was made to sound like it was coming out of the radio, so in a way I was writing source music as well as score. She’s really big and clever about subverting conventional approaches to music in film in general.

SM: Yeah, I actually have a piece of audio I’m going to play for you in a bit from her about your work in Friday Night—

DH: (laughing) Okay.

SM: At what point did you begin writing the music for that film, was it at the script stage, or was it during the rushes or did you wait until the footage was being assembled? Because your music is like a character in that film, and there are certain points where without your music the scenes would play very differently.

DH: Early on. What I did, what I do on most films I work on is to try and get the script quite early and start to get ideas together just from reading and imagining. Because I think that as a composer, if you write from the script before the image, you come up with things you’d never write once the film’s made. And yeah, a lot of that stuff ends up getting thrown out because it doesn’t necessarily work, but you sometimes can get a real body of ideas that stick. You might need to change the tempo, instrumentation, whatever…but if you can somehow get inside the spirit of the script you often find that—if the director is working reasonably close to the script—you find that you’ve kind of gotten inside the film even before they’ve filmed it. And something Claire was always keen on, though we never actually pulled it off, was for the actors to have the music playing when they were acting. Which is something we’ve managed to do on the last film I’ve just done (Ira Sach’s Married Life)…and which Sergio Leone did a lot with Morricone. It’s kind of making music apart of something early on rather than, “Okay we’ve made the film with temp music and everything and now we just need to get a composer to dot the “I’s” and cross the “T’s” and make it all work.” And with Vendredi Soir, quite a few of the pieces end up being on the film that are composed just from the script.

SM: Moving on to Forty Shades of Blue. It’s a funny story, I read an interview where Ira Sachs said they were using Trouble Every Day as the temp score when they were cutting the film and then they were like, “Well why don’t we just get this guy to come in and do the score?” What was it like to get that call?

DH: It’s quite funny, he did just call me up, I was in France on holiday at the time. And I didn’t know what his film was like or anything, so I was like, you know, “Send me what you got.” It was a really interesting film—there’s something about it I really loved—so I got involved.

SM: Now how did you manage to make your work on Forty Shades fresh, while at the same time understanding and respecting that the director wanted your work because of motifs he’d seen in your previous films. Because I guess you can’t give him the Trouble Every Day score but he wants you to do something in that vein, so what’s it like to have an assignment of that nature?

DH: I think it in a way it was less Trouble Every Day and more Friday Night—

SM: I’m glad you said that, because in the interview he only mentions Trouble Every Day, but in the film there are certain pieces that sound very much like Friday Night, though they are different.

DH: I think that’s because Friday Night is not available. His editor, Alfonso, I think he said, “Why don’t we try this?” And I think Ira would have liked his temp to be Friday Night, but here I’m glad he didn’t. Even though it’s good to be able to temp real music, it also is quite tough because when you come in to write something, if what they temp with is working really well, it’s kind of frustrating because you’re kind of having to recreate yourself in a way that can be really difficult. So because they temped more with Trouble Every Day, it wasn’t such a problem. And further, there isn’t a huge amount of music in that score because it’s so much of the source music, the blues and Memphis soul stuff.

SM: And what was that like, to have your music placed right beside this music from the deep American South, that’s a very specific sound coming from Memphis. Was that at all intimidating realizing that your compositions would have to play side by side with this music?

DH: It was tough, but I think in some ways because we actually rerecorded some of the tracks with different artists and things, it wasn’t just a string of classic recordings. At the same time I made some conscious decisions about instrumentation and the way I was gonna do it. Because there wasn’t a budget to do it with an orchestra, I played all the parts myself, to get at a little string section in a way that on some of those old recordings…I was trying to sound a little bit like that in a crude way. It was interesting.

SM: You’re a violinist, correct?

DH: I play violin, guitar and keyboards. But violin is my first, literally.

SM: It seems like in the Friday Night and Forty Shades soundtracks that the piano actually paces the score in those two.

DH: Yeah.

SM: I just thought that was interesting because it didn’t seem like you had as strong a background in piano, but when you approached your compositions, that’s the instrument that dictates the score.

DH: It’s hard to write music on the violin unless it’s going to be a sort of violin piece or a folk piece or something like that. In terms of film, I think most people find it easier to write on keyboard. Having said that, the piano—especially in Vendredi Soir—it was a sound I thought just worked really well in terms of it, it’s got a kind of instant, kind of sharp and powerful, it’s got a kind of feel that just sits right with it. I just used it to write little motifs and the strings are there but they, in a way, are supporting what the piano is doing.

SM: Keeping Mum (2005) is a film of a completely different tone than—

DH: You’ve seen it?

SM: I have seen it.

DH: Okay.

SM: —a completely different tone and it seems like you brought a completely different palette to that film, and it made me think you adjust the instruments in your toolbox to the material you’re working on—

DH: Yeah.

SM: —because that score, it’s fun, it’s all over the place. There’s Hollywood strings, and then there’s even this jazzy, boppy swing thing going on. It seems like that was a lot of fun to work on.

DH: Yeah it was a lot of fun. I think it’s kind of unusual in that I did all the music on it; there’s no source music on it at all, which is really unusual for a modern film. And because of that, I had to sort of cover all the different bases the director was hearing music changing. Stylistically, the biggest challenge in a way was having different styles within a score, but making it all sound like it was a score.

SM: Now how did you come to that gig, because looking at Forty Shades and Friday Night, I would not think, “Hey, this is the guy I want to score, ya know, my…British Comedy?”

(Dickon laughs)

SM: I mean, but it works, you definitely pull it off.

DH: He basically wanted to get some of the…I don’t know, it’s like a black comedy I suppose, and I think he was resisting the comedy staying too sweet and too, I don’t know…superficial. So he approached me because he thought I could do something that would get inside the film a bit more and not just be a sort of happy little comedy school that bubbled along. And I think also there’s some darker elements to the film that he wanted to be brought out with music even in a fun sort of way.

SM: Well, yeah, because you’ve become the dark music guy, right?

DH: The thing with Tindersticks is there’s always a humor in our music that maybe not many people got besides us but—

SM: Well it’s definitely a bit sinister, your music, Tindersticks.

DH: (laughing) Well, yeah, I felt tracks like “My Sister,” though, had an element of dark humor to them, lurking in there somewhere…for me anyway.

SM: Are there film scores you find inspiring or maybe composers, film or otherwise, that you feel have inspired you as a composer?

DH: We listened to film music, and I had an interest in it even as a kid. We used to have this thing called “Saturday Night At The Movies.” Each week it would show an old Errol Flynn film or something like that. Unconsciously I think I was taking in all those old great Hollywood film writers like Korngold and all those guys. I think a lot of them were immigrants who went to America in that early age of Hollywood and…I think they kind of influenced me unconsciously. Then as I got older, I started to realize I really liked people like Elmer Bernstein, Bernard Herman—I’m a big fan of his—you know, John Barrie is another one, Morricone…and it’s something that just sort of over the years, it effected the music in Tindersticks a lot and ended up probably coming out in the film scores.

SM: It’s interesting because Ms. Denis, she actually compares you to Georges Delerue—

DH: Ohhhhhhh, yeah.

SM: I’m going to play this clip for you, and I hope you can hear it, if not we can stop it—

DH: Okay.

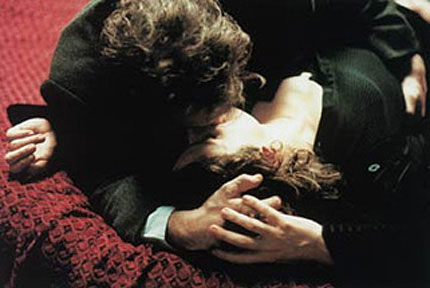

Director Claire Denis speaking over Dickon’s score for Friday Night: "I have to say something about Dickon, about this music…which makes my throat completely…blocked. Because to me it has a quality of a…certain piece of Delerue or Duhamel, for Le Mepris, for Pierrot le fou. It’s kind of, it’s a music that brings…I don’t know, destiny, you know? Kind of like, something that every human being can share which is…a moment, a time. But in the music it contains already that the time is going to end…just like a clock. There is that in what Delerue did for Le Mepris."

(Barry stops the clip)

SM: So did you catch that Dickon?

DH: Yeah, I got most of it. Where was that from?

SM: That is from the commentary on the Friday Night DVD—

DH: Okay, yeah.

SM: It’s during the bedroom scene and I was glad you mentioned the piano earlier the way you did because she mentions it in this way; she feels like you do a very good job communicating time in your scores. And in that film it’s all about time because it’s only one night…and even though the score, it kind of sweeps you away, it reminds you that the time is ticking. When you wrote that piece of music, that piano melody, was that something that was on your mind, or had she articulated that to you?

DH: No, she hadn’t really. That was a piece I wrote very much, much more to picture than a lot of the story. It wasn’t one of the pieces I wrote to the script. And I think it was…I remember coming to the occasion that actually made me write that piece. Because I was really frustrated at the time, and I knew that I needed something important for this scene. I tried lots of things in the vein of the rest of the score that hadn’t worked, and it was something that just came out of two notes, it was like that, the way the piece starts…just a tiny little fragment of a melody that I liked and I just worked on it and just…made it grow into something that started off being very tentative and small into something bigger and more expansive.

SM: It’s a beautiful piece of music.

DH: Thanks.

SM: Do you want to just riff a minute on what it’s like to be a film composer. I mean is this something you can see yourself doing for…the rest of your years? Not to be too grandiose about it.

DH: (laughing) I’ve just finished doing a film, again with Ira Sachs called Married Life. The thing that I like about it is that each film is very different, and even though with this film it’s the same director, it’s a very different kind of film, a different function because it’s set in the 1940s and I’m having to do things I haven’t done before. The thing I love about it is the way it’s sort of a challenge and you kind of--it can drive you mad as well. I mean I don’t like the way you have to be very meticulous in the way you organize yourself and your time and…there are times when you feel very sort of locked in if you’re working on your own compared to say when I’ve worked with bands and things. But at the same time, you’re very much working as part of a big, huge team of people working on a biggish movie, it’s a massive team game and yet you’re spending a lot of time on your own so it’s quite bizarre. But then when you actually get to record the thing and it works and you feel good about it, it’s like a, quite a very satisfying, elevating moment. So…yeah (laughs) I’d like to be carrying on.

SM: And to what degree do you feel like you’re articulating yourself as a musician, because I assume that…. You’re an artist and I think…there must be things you’re consumed with and you’re making these films and I assume that some of that makes its way into the scores. How is that? Is scoring fulfilling in the way you’d expect it to be, or is it more…work?

DH: I think it’s a mixture, I think definitely, you know, I couldn’t do it if I wasn’t being able to express myself. I think to me music is all about expressing who you are, your feelings and communicating that. I wouldn’t be very good at just sort of doing music for functional reasons. And so, what I tend to do is even when I know the music is very much a background element, and it is performing a function in the film, I always kind of make sure it means something to me. And I think because of that, it means that the music can stand up in its own right, away from the image. Which to me is important, I think that film music you can listen to as music; you don’t have to be watching the film at the same time.

SM: Well, I’m right about at the thirty-minute mark, I have one last question—

DH: Yeah, sure.

SM: —that I didn’t get in earlier. In Forty Shades of Blue, the pieces you composed seemed very much to be in the point of view of Laura, they’re really focused around her and what she’s going through. And then you look at a film like Friday Night, you’re setting the tempo, you’re setting the tone. I mean you’re really an equal character in that film. I wanted to know what was the difference in doing those two jobs, and how as a composer, what you get out of those two scenarios.

DH: That’s interesting. With Forty Shades it was very much a conscious decision the first time I saw the film, I thought the score would come from Laura. She needs to have her music because the Rip Torn character, he has his music which is him being a producer, the Memphis music. And so to me to build a musical interaction, she had to have music that was the kind of psychological music of her life, her feelings and emotions. That was a very important thing for me with that film. Also the difference from Friday Night…Ira Sachs described it as like poetry, whereas Forty Shades of Blue is more like a novel. And so in terms of the music there’s an awful lot more space in Claire Denis' work for music; it can occupy a very different kind of space than in most kinds of films. Even someone like Ira, even though his films are very lyrical, there aren’t these sort of long, poetic moments that you get in Claire Denis' films where the music comes to the fore. It’s kind of interesting because the film I’ve just done with him I think is a kind of balance between the two. I think the music definitely has a bigger role than it does in Forty Shades of Blue. But at the same time, it’s still very much driven by dialogue. I think with Claire Denis, because her films aren’t driven by dialogue, they’re driven by…sensuality, and…suggestions of things rather than through language. So the music, it…you know, automatically fulfills it. It has a different sort of role.

SM: Well, thank you for that, I was actually trying to draw you out of a hole there. I think you came out a little bit—

(Dickon laughs his ass off)

SM: —because man, you did a LOT of work on Friday Night, and it really takes that film to a point beyond its narrative.

DH: Oh thanks.

SM: And…thank you for this interview, I wish you all the best of luck. I’m sure you don’t need it.

DH: (laughing) Well, I think I do! Thank you.

For more information visit www.dickon-hinchliffe.com.